What Happened to the Whites Who Killed Eighty-one Blacks During the Colfax Massacre?

| Colfax massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Role of the Reconstruction Era | |||||||

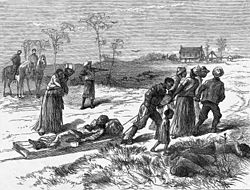

Gathering the dead after the Colfax massacre, published in Harper's Weekly, May ten, 1873 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Courthouse attackers

| Courthouse occupiers

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3 expressionless | Between 62 and 153 expressionless | ||||||

Historical marker in Colfax. Erected in 1950, film taken in 2011. The marker was removed in May 2021.

The Colfax massacre, sometimes referred to by the euphemism Colfax riot, occurred on Easter Sunday, April xiii, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, the parish seat of Grant Parish. An estimated 62-153 blackness militia men were killed while surrendering to a mob of former Amalgamated soldiers and members of the Ku Klux Klan. Iii white men also died in the confrontation.

In the wake of the contested 1872 election for governor of Louisiana and local offices, a grouping of white men armed with rifles and a small cannon overpowered blackness freedmen and state militia occupying the Grant Parish courthouse in Colfax.[1] [two] Nearly of the freedmen were killed later on surrendering, and nearly another l were killed later that dark after existence held as prisoners for several hours. Estimates of the number of dead accept varied over the years, ranging from 62 to 153; three whites died but the number of blackness victims was hard to determine because many bodies were thrown into the Red River or removed for burying, possibly at mass graves.[3]

Historian Eric Foner described the massacre equally the worst case of racial violence during Reconstruction.[1] In Louisiana, it had the most fatalities of any of the numerous tearing events following the disputed gubernatorial contest in 1872 between Republicans and Democrats. Foner wrote, "...every election [in Louisiana] between 1868 and 1876 was marked past rampant violence and pervasive fraud."[4] Although the Fusionist-dominated land "returning board," which ruled on vote validity, initially declared John McEnery and his Democratic slate the winners, the lath eventually split, with a faction declaring Republican William P. Kellogg the victor. A Republican federal judge in New Orleans ruled that the Republican-bulk legislature be seated.[five]

Federal prosecution and conviction of a few perpetrators at Colfax under the Enforcement Acts was appealed to the Supreme Court. In a key instance, the court ruled in Us v. Cruikshank (1876) that protections of the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to the actions of individuals, but only to the deportment of state governments. After this ruling, the federal government could no longer use the Enforcement Deed of 1870 to prosecute actions by paramilitary groups such as the White League, which had chapters forming beyond Louisiana beginning in 1874. Intimidation, murders, and blackness voter suppression by such paramilitary groups were instrumental to the Autonomous Party regaining political command in the state legislature by the late 1870s.

In the belatedly 20th and early 21st centuries, historians accept paid renewed attention to the events at Colfax and the resulting Supreme Court instance, and their meaning in American history, including contemporary history.[6]

State and national background [edit]

In March 1865, Unionist planter James Madison Wells became governor. As the Democratic-dominated legislature passed Black Codes that restricted rights of freedmen, Wells began to lean toward allowing blacks to vote and temporarily disenfranchising ex-Confederates. To attain this, he scheduled a new constitutional convention for July xxx, 1866.[7]

It was postponed because of the New Orleans Massacre that day, in which armed Southern white Democrats attacked blacks who had a parade in support of the convention. Anticipating trouble, the mayor of New Orleans had asked the local military commander to police the city and protect the convention. The U. South. Army failed to promptly reply to the mayor's request and a group of numerous unarmed blacks was attacked by whites, resulting in 38 deaths, 34 black and four white, and more than xl wounded, virtually of them black.[8]

When President Andrew Johnson blamed the massacre on Republican agitation, a popular national backlash against Johnson's policies led to national voters electing a majority Republican Congress in 1866. Information technology passed the Ceremonious Rights Act of 1866 over Andrew Johnson's veto. Earlier, the Freedmen's Bureau and the occupation armies had prevented Southern Black Codes, which had limited the rights of freedmen and other blacks (including their choices of work and living locations), from going into consequence.[ix] [10] On July sixteen, 1866, Congress extended the life of the Freedmen'due south Bureau, also over Johnson's veto. On March 2, 1867, they passed the Reconstruction Deed, over Johnson'southward veto, which required that blacks be given the franchise—in Southern states but not in Northern states—and that reconstructed Southern states ratify the Fourteenth Amendment earlier admission to the Spousal relationship.[11] [12]

By April 1868, a biracial coalition in Louisiana had elected a Republican-bulk country legislature, but violence increased before the fall ballot. Almost all of the victims were black and some white Republicans who were protecting the black Republican freedmen. Insurgents also attacked men physically or burned their homes to discourage them from voting. President Johnson, a Democrat, prevented the Republican governor of Louisiana from using either the land militia or U.Due south. forces to suppress the insurgent groups, such as the Knights of the White Camelia.[13] [ folio needed ]

Background in Grant Parish [edit]

The Crimson River area of Winn and Rapides parishes was a combination of large plantations and subsistence farmers; before the war, African Americans had worked equally slaves on the plantations.[ citation needed ] William Smith Calhoun, a major planter, had inherited a 14,000-acre (57 km2) plantation in the surface area.[14] A one-time slaveholder, he lived with a mixed-race adult female as his common-law wife and had come to support black political equality, encouraging the political organization of the local African-American-based Republican party.[15]

On election 24-hour interval in Nov 1868, Calhoun led a group of freedmen to vote.[ citation needed ] The ballot box was originally at a store owned by John Hooe,[xvi] who had threatened to whip freedmen "if they voted Republican".[17] Calhoun arranged for the election box to exist switched to a plantation store owned past a Republican.[ citation needed ] In add-on, he oversaw the submission of 150 black votes from freedmen on his plantation state.[18] The Republicans received 318 votes, and the Democrats received 49.[nineteen] A group of whites threw the ballot box into the Cerise River, and Democrats arrested Calhoun, alleging election fraud.[ citation needed ] With the original ballot box gone, Democrat Michael Ryan went on to claim a landslide victory.[xx] [ clarification needed ]

The election was also marked by violence.[ citation needed ] Ballot commissioner Hal Frazier, a blackness Republican, was murdered by whites.[21] After this, Calhoun drafted a bill to create a new parish out of parts of Winn and Rapides parishes, which passed the Republican legislature; as a major planter, Calhoun idea he would accept more political influence in the new parish, which had a blackness majority.[ citation needed ] Other new parishes were created past the Republican state legislature to attempt to develop areas of Republican political back up.[ citation needed ]

Enforcement against the Klan [edit]

According to Lane, after Ulysses S. Grant became President in 1869, he "lobbied difficult for the Fifteenth Amendment" (ratified February 3, 1870),[22] which guaranteed that black men, most of whom were newly freed slaves, would accept the right to vote.[23] Nonetheless, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) continued tearing attacks and killed scores of blacks in Arkansas, Due south Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi and elsewhere.[24] In response, on May 31, 1870, Congress passed an Enforcement Act which prohibited groups of people from banding together to violate citizens' constitutional rights.[25] Soon afterwards on Apr 20, 1871, Congress passed the Ku Klux Klan Human action, which Grant used to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and sent federal troops to S Carolina, a state with particularly egregious Klan activity.[26]

Louisiana and Grant Parish [edit]

Governor Henry Clay Warmoth struggled to maintain political balance in Louisiana. Amidst his appointments, he installed William Ward, a black Wedlock veteran, every bit commanding officer of Visitor A, sixth Infantry Regiment, Louisiana State Militia, a new unit to exist based in Grant Parish to aid command the violence there and in other Red River parishes. Ward, built-in a slave in 1840 in Charleston, South Carolina, had learned to read and write as a valet to a chief in Richmond, Virginia. In 1864 he escaped and went to Fortress Monroe, where he joined the Union Army and served until after General Robert E. Lee's surrender. Virtually 1870 he came to Grant Parish, where he had a friend. He chop-chop became agile amidst local blacks in the Republican Party. Later on his appointment to the militia, Ward recruited other freedmen for his forces, several of whom were veterans of the war.[27]

Louisiana election of 1872 [edit]

In Louisiana, Republican governor Henry Clay Warmoth defected from the Liberal Republicans (a group that opposed President Grant'south Reconstruction policies) in 1872. Warmoth previously supported a ramble amendment that immune former Confederates, who had been denied the right to vote, to be re-enfranchised. A "Fusionist" coalition of Liberal Republicans and Democrats nominated ex-Confederate battalion commander and Democrat John McEnery to succeed him as governor. In return, Democrats and Liberal Republicans were to send Warmoth to Washington as a U.S. Senator. Opposing McEnery was Republican William Pitt Kellogg, i of Louisiana'south U.S. Senators. Voting on Nov 4, 1872, resulted in dual governments, equally a Fusionist (Liberal Republicans and Democrat)-dominated returning board declared McEnery the winner while a faction of the board proclaimed Kellogg the winner. Both administrations held inaugural ceremonies and certified their lists of local candidates.

After declining to win their example in country courtroom, the Kellogg forces appealed to federal judge Edward Durell in New Orleans to intervene and lodge that Kellogg and the Stalwart Republican-majority legislature were to be seated, and for Grant to qualify U.S. army troops to protect Kellogg'south authorities. This activeness was widely criticized across the nation by Democrats and both wings of the Republican Party because it was considered to be a violation of the rights of states to manage their ain (not-federal-office) elections. Thus, investigating committees of both chambers of the federal Congress in Washington were critical of the Kellogg selection. The House majority ruled Durell'due south activeness illegal and the Senate majority ended that the Kellogg authorities was "not much meliorate than a successful conspiracy." In 1874 a Firm investigating committee in Washington recommended that Approximate Durell exist impeached for corruption and illegally interfering in the Louisiana 1872 state elections, but the judge resigned in club to avoid impeachment.[28] [29]

McEnery'due south faction tried to take control of the state arsenal at Jackson Foursquare, but Kellogg had the state militia seize dozens of leaders of McEnery's faction and control New Orleans, where the country regime was located.[13] [ folio needed ] McEnery returned to endeavour to take control with a private paramilitary group. In September 1873 his forces, over 8,000 strong, entered the city and defeated the city/state militia of about 3500 in New Orleans. The Democrats took command of the state house, arsenal and police force stations, where the land government was then located, in what was known as the Battle of Jackson Foursquare. His forces held those buildings for 3 days before retreating before Federal troops arrived.[four] [30] Warmoth was subsequently impeached by the state legislature in a blackmail scandal stemming from his actions in the 1872 ballot.

Warmoth appointed Democrats equally parish registrars, and they ensured the voter rolls included as many whites and as few freedmen as possible. A number of registrars changed the registration site without notifying blacks. They also required blacks to testify they were over 21, while knowing that former slaves did not take birth certificates. In Grant Parish, one plantation owner threatened to expel blacks from homes they rented on his state if they voted Republican. Fusionists also tampered with ballot boxes on ballot mean solar day. I was found with a hole in information technology, apparently used for stuffing the ballot box. As a result, Grant Parish Fusionists claimed a landslide victory, even though blackness voters outnumbered whites by 776 to 630.

Warmoth issued commissions to Fusionist Democrats Alphonse Cazabat and Christopher Columbus Nash, elected parish judge and sheriff, respectively. Similar many white men in the S, Nash was a Confederate veteran (as an officeholder, he had been held for a yr and a half as a pow at Johnson's Island in Ohio). Cazabat and Nash took their oaths of function in the Colfax courthouse on January 2, 1873. They dispatched the documents to Governor McEnery in New Orleans.

William Pitt Kellogg issued commissions to the Republican slate for Grant Parish on January 17 and 18. By then Nash and Cazabat controlled the pocket-sized, primitive courthouse. Republican Robert C. Register insisted that he, not Alphonse Cazabat, was the parish judge and that Republican Daniel Wesley Shaw, not Nash, was to be the sheriff. On the dark of March 25, the Republicans seized the empty courthouse and took their oaths of office. They sent their oaths to the Kellogg administration in New Orleans.[13] [ page needed ]

Grant Parish was 1 of a number of new parishes created by the Republican government in an effort to build local support in the state. Both the land and its people were originally tied to the Calhoun family, whose plantation had covered more than than the borders of the new parish. The freedmen had been slaves on the plantation. The parish also took in the less-developed loma country. The total population had a narrow majority of 2400 freedmen, who mostly voted Republican, and 2200 whites, who voted as Democrats. Statewide political tensions were reflected in the rumors going around each community, often about white fears of black attacks or outrage, which added to local tensions.[31]

Colfax courthouse conflict [edit]

Fearful that the Democrats might attempt to take over the local parish government, black people started to create trenches effectually the courthouse and drilled to keep alert. The Republican officeholders stayed at that place overnight. They held the town for three weeks.[32]

On March 28, Nash, Cazabat, Hadnot and other white Fusionists called for armed whites to retake the courthouse on April 1. Whites were recruited from nearby Winn and surrounding parishes to join their try. The Republicans Shaw, Register, and Flowers and others began to collect a posse of armed blacks to defend the courthouse.[thirteen] [ page needed ]

Black Republicans Lewis Meekins and state militia captain William Ward, a black Union veteran, raided the homes of the opposition leaders: Gauge William R. Rutland, Pecker Cruikshank, and Jim Hadnot. Gunfire erupted between whites and blacks on April 2 and again on April 5, but the shotguns were too inaccurate to do any harm. The two sides bundled for peace negotiations. Peace concluded when a white human shot and killed a black homo named Jesse McKinney, described equally a bystander. Another armed conflict on April 6 concluded with whites fleeing from armed blacks.[33] With all the unrest in the community, black women and children joined the men at the courthouse for protection.

William Ward, the commanding officer of Visitor A, 6th Infantry Regiment, Louisiana State Militia, headquartered in Grant Parish, had been elected land representative from the parish on the Republican ticket.[34] He wrote to Governor Kellogg seeking U.South. troops for reinforcement and gave the letter to William Smith Calhoun for commitment. Calhoun took the steamboat LaBelle down the Cherry-red River but was captured by Paul Hooe, Hadnot, and Cruikshank. They ordered Calhoun to tell blacks to go out the courthouse.

The blackness defenders refused to leave although threatened by parties of armed whites allowable past Nash. To recruit men during the rising political tensions, Nash had contributed to pulp rumors that blacks were preparing to kill all the white men and have the white women every bit their own.[35] On Apr viii the anti-Republican Daily Petty paper of New Orleans inflamed tensions and distorted events past the following headline:

THE RIOT IN GRANT PARISH. FEARFUL ATROCITIES Past THE NEGROES. NO RESPECT SHOWN TO THE Dead.[36]

Such news attracted more whites from the region to Grant Parish to join Nash; all were experienced Confederate veterans. They acquired a 4-pound cannon that could burn down iron slugs. As the Klansman Dave Paul said, "Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy."[37]

Suffering from tuberculosis and rheumatism, on Apr 11 the militia captain Ward took a steamboat downriver to New Orleans to seek armed help directly from Kellogg. He was not at that place for the following events.[38]

Massacre [edit]

Cazabat had directed Nash as sheriff to put down what he called a anarchism. Nash gathered an armed white paramilitary grouping and veteran officers from Rapides, Winn and Catahoula parishes. He did not movement his forces toward the courthouse until noon on Easter Sunday, April 13. Nash led more than 300 armed white men, nigh on horseback and armed with rifles. Nash reportedly ordered the defenders of the courthouse to leave. When that failed, Nash gave women and children camped exterior the courthouse thirty minutes to clear out. Afterwards they left, the shooting began. The fighting continued for several hours with few casualties. When Nash'due south paramilitary maneuvered the cannon behind the building, some of the defenders panicked and left the courthouse.

Most 60 defenders ran into nearby forest and jumped into the river. Nash sent men on horseback after the fleeing black Republicans, and his paramilitary group killed near of them on the spot. Soon Nash's forces directed a blackness convict to set the courthouse roof on fire. The defenders displayed white flags for surrender: one made from a shirt, the other from a page of a book. The shooting stopped.

Nash's group approached and called for those surrendering to throw down their weapons and come exterior. What happened next is in dispute. According to the reports of some whites, James Hadnot was shot and wounded by someone from the courthouse. "In the Negro version, the men in the courthouse were stacking their guns when the white men approached, and Hadnot was shot from behind by an overexcited member of his own force."[39] Hadnot died later on, after being taken downstream by a passing steamboat.[xl]

In the aftermath of Hadnot's shooting, the white paramilitary grouping reacted with mass murders of the black men. As more than forty times equally many blacks died as did whites, historians describe the effect as a massacre. The white paramilitary group killed unarmed men trying to hide in the courthouse. They rode down and killed those attempting to abscond. They dumped some bodies in the Red River. About 50 blacks survived the afternoon and were taken prisoner. Later that night they were summarily killed by their captors, who had been drinking. Only one black man from the grouping, Levi Nelson, survived. He was shot by Cruikshank but managed to crawl away unnoticed. He later served as one of the Federal government's primary witnesses confronting those who were indicted for the attacks.[41]

Kellogg sent state militia colonels Theodore DeKlyne and William Wright to Colfax with warrants to abort 50 white men and to install a new, compromise slate of parish officers. DeKlyne and Wright found the smoking ruins of the courthouse at Colfax, and many bodies of men who had been shot in the dorsum of the head or the neck. They described that 1 body was charred, another human'due south head beaten beyond recognition, and another had a slashed throat. Surviving blacks told DeKlyne and Wright that blacks dug a trench effectually the courthouse to protect it from what they saw as an attempt past white Democrats to steal an election. They were attacked by whites armed with rifles, revolvers and a small cannon. When blacks refused to leave, the courthouse was burned, and the black defenders were shot down. While the whites accused blacks of violating a flag of truce and rioting, black Republicans said that none of this was true. They accused whites of marching captured prisoners away in pairs and shooting them in the back of the head.[13] [ page needed ]

On April xiv some of Governor Kellogg's new law force arrived from New Orleans. Several days later on, two companies of Federal troops arrived. They searched for white paramilitary members, but many had already fled to Texas or the hills. The officers filed a military report in which they identified past proper name iii whites and 105 blacks who had died, plus noted they had recovered fifteen-20 unidentified blacks from the river. They likewise noted the brutal nature of many of the killings, suggesting an out-of-control situation.[42]

The exact number of dead was never established: two U.S. Marshals, who visited the site on Apr xv and cached dead, reported 62 fatalities;[43] a military report to Congress in 1875 identified 81 blackness men by name who had been killed,[44] and besides estimated that between 15 and 20 bodies had been thrown into the Red River, and some other eighteen were secretly buried, for a chiliad total of "at to the lowest degree 105";[45] a state historical marker from 1950 noted fatalities as three whites and 150 blacks.[46]

The historian Eric Foner, a specialist in the Civil State of war and Reconstruction, wrote virtually the event:

The bloodiest single example of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era, the Colfax massacre taught many lessons, including the lengths to which some opponents of Reconstruction would go to regain their accustomed dominance. Among blacks in Louisiana, the incident was long remembered as proof that in any large confrontation, they stood at a fatal disadvantage.[one]

"The organization against them is too strong. ..." Louisiana blackness teacher and Reconstruction legislator John G. Lewis later remarked. "They attempted [armed cocky-defense] in Colfax. The result was that on Easter Dominicus of 1873 when the sun went down that night, it went down on the corpses of two hundred and eighty negroes."[1]

Aftermath [edit]

James Roswell Beckwith, the US Attorney based in New Orleans, sent an urgent telegram well-nigh the massacre to the U.S. Attorney General. The massacre in Colfax gained headlines of national newspapers from Boston to Chicago.[47] Various government forces spent weeks trying to round upwards members of the white paramilitaries, and a total of 97 men were indicted. In the end, Beckwith charged 9 men and brought them to trial for violations of the Enforcement Human activity of 1870. It had been designed to provide federal protection for civil rights of freedmen nether the 14th Amendment against actions by terrorist groups such as the Klan.

The men were charged with 1 murder, and charges related to a conspiracy against the rights of freedmen. In that location were two succeeding trials in 1874. William Burnham Woods presided over the first trial and was sympathetic to the prosecution. Had the men been convicted, they would not have been able to appeal their decision to any appellate court according to the laws of the time. Even so, Beckworth was unable to secure a conviction—i man was acquitted, and a mistrial was alleged in the cases of the other eight.

In the 2nd trial, 3 men were found guilty of sixteen charges. However, the presiding judge, Joseph Bradley of the United states of america Supreme Court (riding circuit), dismissed the convictions, ruling that the charges violated the state actor doctrine, failed to evidence a racial rationale for the massacre, or were void for vagueness. Sua sponte, he ordered that the men be released on bail, and they promptly disappeared.[13] [ page needed ] [48]

When the federal regime appealed the instance, it was heard by the US Supreme Court as United States v. Cruikshank (1875). The Supreme Courtroom ruled that the Enforcement Human activity of 1870 (which was based on the Bill of Rights and 14th Amendment) applied just to actions committed by the land and that it did not apply to actions committed by individuals or private conspiracies (See, Morrison Remick Waite). This meant that the Federal government could not prosecute cases such as the Colfax killings. The court said plaintiffs who believed their rights were abridged had to seek protection from the state. Louisiana did not prosecute any of the perpetrators of the Colfax massacre; nigh southern states would not prosecute white men for attacks confronting freedmen. Thus, enforcement of criminal sanctions under the act ended.[49]

The publicity nigh the Colfax Massacre and subsequent Supreme Courtroom ruling encouraged the growth of white paramilitary organizations. In May 1874, Nash formed the first affiliate of the White League from his paramilitary group, and chapters shortly were formed in other areas of Louisiana, as well as the southern parts of nearby states. Unlike the erstwhile KKK, they operated openly and often curried publicity. 1 historian described them as "the military arm of the Democratic Party."[50] Other paramilitary groups such as the Crimson Shirts likewise arose, specially in South Carolina and Mississippi, which also had black majorities of population, and in certain counties in North Carolina.

Paramilitary groups used violence and murder to terrorize leaders amid the freedmen and white Republicans, too as to repress voting amid freedmen during the 1870s. Black American citizens had little recourse. In Baronial 1874, for instance, the White League threw out Republican officeholders in Coushatta, Red River Parish, assassinating the half dozen whites before they left the land, and killing five to fifteen freedmen who were witnesses. Four of the white men killed were related to the state representative from the area.[51] Such violence served to intimidate voters and officeholders; it was one of the methods that white Democrats used to gain command of the state legislature in the 1876 elections and ultimately to dismantle Reconstruction in Louisiana.

Memorials [edit]

The scale of the massacre and the political conflict it represents are of state and national significance in relation to Reconstruction and Usa racial histories.[six] Despite this, the event has been hidden in local history for decades.[ citation needed ] Moreover, the site has changed: some of the areas have been paved, and the old courthouse was torn down and a new courthouse was built.[ citation needed ] Finally, without archeological work to establish where victims were buried at the site, people have had difficulty defining a site to gain approval for a historic memorial.[ citation needed ]

In 1920, a committee met in Colfax to purchase a monument to memorialize the three white men who died. This monument stands in Colfax Cemetery and reads "Erected to the memory of the Heroes, / Stephen Decatur Parish / James Due west Hadnot / Sidney Harris / Who fell in the Colfax Riot fighting for White Supremacy."[52] [53]

In 1950, Louisiana erected a thruway marker noting the result of 1873 equally "the Colfax Riot," as the outcome was traditionally called in the white community. The marking states, "On this site occurred the Colfax Riot, in which 3 white men and 150 negroes were slain. This event on April xiii, 1873, marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the Due south."[49] [52] [54] The marking[55] was removed on May 15, 2021, for eventual placement in a museum.[56]

Renewed attention [edit]

The Colfax massacre is among the events of Reconstruction and tardily 19th-century history which accept received new national attending in the early 21st century, much as the 1923 massacre in Rosewood, Florida did most the end of the 20th century. In 2007 and 2008 two new books were published on the topic: Leeanna Keith'south The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, and the Death of Reconstruction,[57] and Charles Lane'due south The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction. [58] Lane especially addressed the political and legal implications of the Supreme Court case, which arose out of the prosecution of several men of the white paramilitary groups.[ citation needed ] In add-on, a film documentary is in preparation.[ citation needed ]

In 2007 the Ruddy River Heritage Clan, Inc. was formed as a group intending to establish a museum in Colfax for collecting materials and interpreting the history of Reconstruction in Louisiana and particularly the Ruddy River surface area.[ citation needed ]

In 2008, on the 135th anniversary of the Colfax massacre, an interracial grouping commemorated the event. They laid flowers where some victims had fallen and held a forum to talk over the history.[59]

See also [edit]

- Listing of incidents of civil unrest in the U.s.

- List of massacres in Louisiana

Notes [edit]

- ^ a b c d Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, p. 437

- ^ Ulysses South. Grant, People and Events: "The Colfax Massacre", PBS Website, accessed April 6, 2008

- ^ "In a modest Louisiana town, two monuments to white supremacy stand up on public basis". Southern Poverty Law Centre . Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, New York: Perennial Library, 1989, p. 550

- ^ Lane 2008, p. b13

- ^ a b William Briggs and Jon Krakauer (August 28, 2020). "The Massacre That Emboldened White Supremacists". The New York Times.

- ^ Holt, Michael (2008). Past One Vote. Lawrence, Kansas: University Printing of Kansas. pp. 195–96.

- ^ Craven, Avery (1969). Reconstruction. Boston: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. pp. 186–87.

- ^ Simkins, Francis; Roland, Charles (1947). A History of the Southward. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 262.

- ^ Ezell, John (1975). The South Since 1865. New York: Macmilan. pp. 47–viii.

- ^ Randall, J. G.; Donald, David (1961). The Ceremonious War and Reconstruction. Boston: D. C. Heath. pp. 633–34.

- ^ "U.S. Senate: The Civil War: The Senate's Story". www.senate.gov . Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Lane 2008

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Fellman, M. (2008). The Journal of American History, 95(2), 550-551. doi:ten.2307/25095698

- ^ Keith, LeeAnna (January 28, 2008). The Colfax massacre : the untold story of Blackness ability, White terror, and the death of Reconstruction. Oxford University Printing. p. 60. ISBN9780195310269.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. ii.

- ^ Keith, LeeAnn (January 28, 2008). The Colfax massacre : the untold story of Black power, White terror, and the death of Reconstruction. Oxford Academy Press. p. threescore. ISBN9780195310269.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 41

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 41f

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 1f

- ^ "Our Documents - 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Voting Rights (1870)". www.ourdocuments.gov . Retrieved March ii, 2021.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 3f

- ^ "U.S. Senate: The Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871". www.senate.gov . Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ "The Ku Klux Klan and Violence at the Polls". Bill of Rights Institute . Retrieved March 2, 2021.

- ^ Lane 2008, pp. 44–56.

- ^ William Hesseltine, "Grant the Politician", 344

- ^ Charles Lane, *The Green Bag*, "Edward Henry Durell," 167-68

- ^ Wert, Jeffry (1993). General James Longstreet. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 416.

- ^ James 1000. Hogue, "The Boxing of Colfax: Paramilitarism and Counterrevolution in Louisiana", 2006, accessed August 15, 2008

- ^ Keith, LeeAnna (2008). The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction . New York: Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN978-0-19-531026-nine.

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 154

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 56

- ^ Keith (2007), The Colfax Massacre, p. 117

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 84

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 91

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 57

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Boxing of the Civil State of war, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, paperback, 2007, p.18

- ^ Lemann (2007), Redemption, p. 18

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 124

- ^ "Military Study on Colfax Riot, 1875", Congressional Tape], accessed April 6, 2008

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 265

- ^ Find a grave memorial on the Colfax Massacre has 80 names listed

- ^ Lane 2008, pp. 265–66

- ^ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism (1950). "Colfax Riot Historical Marker".

- ^ Lane 2008, p. 22

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Ceremonious War, New York; Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006, p.25

- ^ a b Velez, Denise Oliver (April 12, 2020). "The Easter massacre of 1873—and the subsequent Supreme Court decision that sabotaged Reconstruction". Daily Kos . Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ Eric Foner (2002),Reconstruction, p. 551

- ^ a b Rubin, Richard (July–August 2003). "The Colfax Riot". The Atlantic Monthly . Retrieved June x, 2009.

- ^ Colfax Riot Memorial at Detect a Grave

- ^ Keith (2007), Colfax Massacre, p. 169

- ^ "Colfax Riot". Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Lane, Charles (June nine, 2021). "Opinion: Not far from Tulsa, a quieter but consequential correction of the historical record". The Washington Post . Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Keith 2007.

- ^ Lane 2008.

- ^ LeeAnna Keith, "History is a Gift: The Colfax Massacre", Blog: Oxford University Press, April 17, 2008; accessed Baronial 13, 2008

References [edit]

- Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America'due south Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row.

- Goldman, Robert M., Reconstruction & Blackness Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank, Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

- Hogue, James K., Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battle and the Rising and Autumn of Radical Reconstruction, Billy Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

- Keith, Leeanna (2007). The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Decease of Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0195393088.

- KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, second Session, Senate Report 693.

- Lane, Charles (2008). The Solar day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Expose of Reconstruction . New York: Henry Holt & Visitor. ISBN9781429936781.

- Lemann, Nicholas, Redemption: The Last Boxing of the Civil War 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Rubin, Richard, "The Colfax Riot", The Atlantic, Jul/Aug 2003

- Taylor, Joe Grand., Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974, pp. 268–70.

External links [edit]

- Ulysses S. Grant, People and Events: "The Colfax Massacre", 1997-2001 Public Broadcasting Organisation

- "Armed forces Study on Colfax Anarchism, 1875", The Congressional Record

- Country Highway Marker on Google Street View

Coordinates: 31°31′01″North 92°42′42″W / 31.51691°N 92.71175°W / 31.51691; -92.71175

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colfax_massacre

0 Response to "What Happened to the Whites Who Killed Eighty-one Blacks During the Colfax Massacre?"

Post a Comment